While growing up aboard in the 1950s, I enjoyed Horatio Alger stories where poverty-stricken lads achieved their dreams through diligence and sustained hard work. Growing up poor does that to you—makes you grasp at any improbable tale where the poor man ultimately triumphs.

We Goodlanders, despite owning a boat, had no TV. We couldn’t even afford to see a motion picture ashore, not with Eisenhower in office. The only books we possessed were from the dusty shelves of Goodwill and Sally’s Army—dogeared twenty-cent copies of How to Win Friends and Influence People.

Owning a record player was out of the question—and even if we did, we couldn’t have afforded the 78s. If we wanted music as a family, we sang Barbershop tunes together.

Food was scarce; leather shoes even scarcer.

Here’s the truth: we had such little money all I could aspire to as a wayward youth was to steal a pen and become an F. Scott Fitzgerald or an Ernest Hemingway.

Sadly, that was about as likely as being struck by lightning. Even if I could borrow a pencil stub, cigar-chomping, old-money publishers resolutely blocked my path. They collected the lion’s share of the profit—most writers in the 1950s were, at best, allowed to pick through the offal.

A few generations after mine, however, most families could afford TVs. They didn’t want to be writers—their heroes wore make-up. They wanted to be on television as they watched Lloyd Bridges’ Sea Hunt, McHale’s Navy, and Adventures in Paradise (created by James Michener).

A few generations after mine, however, most families could afford TVs. They didn’t want to be writers—their heroes wore make-up. They wanted to be on television as they watched Lloyd Bridges’ Sea Hunt, McHale’s Navy, and Adventures in Paradise (created by James Michener).

Which generation am I talking about? Think S/V Devos & crew.

If you like Cap’n Fatty Goodlander, You’ll love these:

- Troubleshooting 12 volt Electric – Fatty Style

- How to Safely Anchor a Boat – The Ultimate Guide

- Saying No!

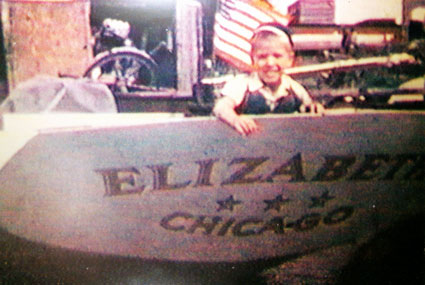

Anyway, I lived aboard and I didn’t go to school because I handline fished all day to fill our bellies. I tended my crab pots, I speared flounder, and I harvested shellfish from the pilings the half-rotten schooner Elizabeth was tied to. Alas, at the end of the 1950s my father, an itinerant sign-painter, was diagnosed with Parkinson’s. We had to sell our beloved boat and move to a hillbilly trailer park just outside Chicago.

Ashore, I immediately felt like a Stranger in a Strange Land. I’d never really gone to school—just a couple of months here and there. I didn’t like school. Worse, school didn’t like the barefoot, unwashed me.

At 15 years of age, I purchased Corina, a wooden 22-foot double-ender. I left home. I left school. I stopped trying to please landlubbers and met my wife-to-be. Yes, 1968 was an interesting year for the entire world—and particularly pivotal for me.

But I had a problem: I couldn’t draw a bath—so I couldn’t aspire to be a sign painter. I had no graphic talent. Zero! Hell, I couldn’t even draw on a cigarette! Just to make matters worse, I had a speech impediment. People would say stuff like, “Gee, you sound even dumber than you look!”

However, my father hadn’t been born with a brush in his fist—he’d learned his trade. Why had he chosen sign painting as a profession? He hadn’t. He’d just done what he’d enjoyed—and eventually figured out a way to get paid for it.

Who knows how and why we are the way we are? DNA? Random chance? Some vague snatch of conversation overheard in the womb?

Around the age of five I started collecting pens. Yes, I collected knives and cigarette lighters as well—but it was writing instruments that thrilled me.

I worked on boats as a kid. I checked their bilges for absentee owners. I would occasionally buy notebooks—and fill them with erotic poetry, song lyrics, and, eventually, love letters to my wife. By the middle of the 1970s, my life dream was clear—I wanted to be a writer.

A writer? With only a few years of spotty education? While knowing nothing of grammar, punctuation, or how to spill? (Spyell? Speal? Speel?)

Yeah. A writer. Why shouldn’t a delusional illiterate dream big?

As a writer, I only had one natural, God-given strength—I realized my writing sucked. Many writers are in love with their words for the sole reason that their words are their words—not so, in my case.

But a dream, no matter how noble, will always remain a dream without specific action directed at an achievable goal. So, I approached my bewildered wife and made my pitch.

“How about you support me for one year while I scribble?”

Being love-struck and gullible, she agreed.

We were in a strange town—St. Augustine, Florida, at the time—and I knew no one. So, I went to the local librarian and pled my case: I’d only gone to school for a few years and wanted to become a writer—would she help?

“How,” asked Mrs. Louise Darby, the head librarian of the St. Johns County Library system.

“Well, I need a place to write uninterrupted for a year.”

“And you’ve never been published?”

“No.”

“Did you bring a sample of your writing?”

“No.”

“And you have no money to pay rent.”

“…not a penny,” I admitted.

“Why ask me?” she asked, genuinely puzzled. “Do you really think you can just walk in off the street and ask for such a thing—I don’t know you, don’t know a single thing about you.”

“Why you?” I asked, starting to deflate. “Well, I figured if libraries encouraged the reading of books, that they’d encourage the writing of them as well—that makes sense, doesn’t it?”

Ah, fate is an interesting thing. And the fact that, as Buddha says, “When the student is ready, the teacher arrives.”

“Follow me, young man,” Mrs. Darby said. She led me upstairs to a dusty garret above the library at 12 Aviles Street that I didn’t know existed—the writing room where Pulitzer Prize (1939) winner Marjorie Kinnan Rawlings had written and edited The Yearling while not at her beloved Cross Creek.

Wow! Holy feces! Fate! Celestial encouragement! Cosmic reinforcement!

“Don’t disappoint me,” Mrs. Darby said as she left. (I did not. For the next decade or two until her death, I kept her abreast of my literary career.)

Thus, I now had a posh office, a year ahead of me, an Olivetti portable typewriter, and a few dozen sheets of typing paper. Only one problem—I had no words. None. I’d vaguely dreamt of this moment my entire adult life—when I’d magically metamorphosize into a writer—but. Now. I. Had. No. Words!

None.

Not a freak’n one!

I was flabbergasted—totally shocked. My wife was waiting on tables. She believed in me. I didn’t want to disappoint her. Mrs. Darby, a complete stranger, also believed in me. But I was not worthy of their belief. I was a fraud, a dreamer; a literary poseur.

I was horrified.

Occasionally, I’d type a sentence, re-read it, edit it, polish it, change-it, add-to-it, cut a phrase, take out an adverb… and stare at it some more—than scream and rip the sheet out of the typewriter and angrily toss it on the floor in utter, angry frustration.

The only reason I didn’t punch holes in the wall with my fist was because the walls weren’t mine.

For the first time in my young life, I questioned if I was a loser. Sure, I was a drop-out. But loser? Was I a loser? My initial goal was modest—to write something, anything, that sold within the next year. But that goal was far, far too ambitious when I couldn’t write a simple declarative sentence—let alone, a whole paragraph.

And my wife was humping tables—what a selfish, rat-bastard I was!

I gradually began to think this ‘writing’ concept was totally beyond me. However, I could type. So, I rolled a sheet of paper into my typewriter, and typed as fast as I could… all the depressing thoughts running through my mind. “My Olivetti is bluish-green. It is Tuesday. I’m wearing shorts, blue seven-pocket sailing shorts. My wife’s name is Carolyn. I live on a boat called Carlotta. We built it. From scratch. In Boston. Oh, sh*t! Those aren’t complete sentences. I should write in complete sentences. That’s how they do it—whomever ‘they’ are. Anyway, I just wrote a paragraph and I’m going to write another ‘graph about… anything that jumps into my mind because I can’t write but I can type and thus I will type because I don’t give up and I don’t quit and I have grit and I won’t disappoint my wife and Mrs. Darby and, worse of all, disappoint myself! So, I type. And type. And type some more. I will write anything that pops into my head. For example, it is ten in the morning. I want a cup of coffee but can’t afford one. Besides, I’m here in this lovely, sacred office to berate myself, not drink coffee…”

Occasionally, I’d grind to halt and once I realized that I was stopped, I’d shout aloud to the room, “Don’t think, you f’n fool, type!” I read every book in the library on writing. I went to the local paper and demanded to speak with a writer. They gave me to Katherine Hawk, their business columnist, whom I still correspond with forty years later. Jack Hunter was a best-selling novelist who lived in town—I introduced myself. He regaled me with tales of Hollywood. A number of his books (The Blue Max, in particular) had been made into popular movies. A British novelist (Time Most Precious) by the name of Margaret Walters visited Florida. I offered to drive her around the state while she lectured to various writer’s groups—all of which I networked with.

And I changed my personal professional goal from getting published once in the first year to collecting 100 honest rejection slips. Hell, that would be easy—my writing was utter crap!

Every day for 4 to 6 hours, I typed. And typed some more. Sadly, typing paper costs money. A ream at the time cost $5.20 cents. I’d go through more than a ream a month—and money was tight.

Once I was done with those sheets of paper, they were utterly worthless. I’d ruined their value. Yeah, depressing!

So, instead, I bought a giant roll of white butcher paper—and fed it, via a string from the ceiling through its cardboard tube—into my typewriter carriage.

Every time I stopped putting words on the page, I’d angrily shout out, “Type, you stupid sumbitch, type!” Occasionally, I’d send out manuscripts—which I began to call my ‘homing pigeons’ because they’d always head straight back home.

One irritated editor wrote at the bottom of one of my freelance submissions, “Do you realize, Mister Goodlander, that trees have to die so you can write this dribble?”

At the very end of the year—with nearly a hundred rejection slips from the New Yorker to Mad Magazine; Marty Luray of SAIL magazine purchased my first national marine article. I cried. Hell, I just broke down and cried. I wept like a baby.

…hell, I just cried again 40-odd years later while remembering it—that sweet, blessed moment of literary vindication.

That single paragraph letter of acceptance on SAIL magazine letterhead was—and still is—the most important thing to have ever happened to me professionally. I wasn’t a gigolo living off my wife any longer, I was a commercial wordsmith learning his craft.

This check for $250 was proof—so I kissed it and raised my eyes to the heavens in appreciation.

I also immediately sent Marty another sea yarn entitled The Last Cruise. Upon its publication, SAIL magazine received more positive mail than from any other story it had ever published.

“You’re on your way, Fatty,” said Marty. “I predict great things—you have the fire!”

From that day on, I’ve never been out of print—not once, not ever!

Ten years later, I collected some of my published pieces in a modest book—and was amazed when otherwise sane people brought copies of it. Actually, the highest compliment that I can get as a writer is to have someone recommend one of my books to a friend. There is no higher compliment for an inkslinger than that.

Once I conquered my speech impediment, I started working in radio as well. This culminated after twenty years (on Radio One WVWI) with a summer series on NPR. (Some episodes are still archived on the NPR website.)

In 1990, I decided to write a book from scratch. Since I’d trained myself to be facile, I did exactly that. I intended to send it off to small unknown publishers, but a fellow writer told me not to be silly, to send it to the most prestigious publisher in the world—the New York publisher who had published all my literary and sailing heroes.

Thus, I sent the book manuscript off to Lothar Simon of Sheridan House. A short week later, he wrote me back and told me that he’d buy it. I was in shock, utter shock. I couldn’t believe it. I must have read the letter a hundred times before taking my wife out to a fancy champagne dinner—to pop both the cork and the news.

Being prudent, however, I researched Sheridan House. They didn’t pay much and only kept a book in print for 18 months—but still, my foot would be in the door. I called up Lothar, introduced myself, and froze when he said, “Well, in order to publish your manuscript, we’ll have to cut all that stuff about drugs, sex, and rock & roll.”

WTF?

What would be left—another boring cruising yarn of ‘at three in morning, with a nor’easterly blowing 35 and gusting to 40 knots, we handed the jib and hoisted our storm staysail…?”

I was utterly horrified to hear myself boldly say to Lothar, “No, thanks! I’m not going to cut all the funny parts out of a book intended to make sailors laugh.”

That was over 30 years ago. I formed American Paradise Publishing and came out with Chasing the Horizon within a few months. While it got off to a slow start, word-of-mouth was kind. It sold better each year for 23 straight years—and still continues to sell well to this day. It alone has earned me more than $100,000. Jeff at Amazon invented Kindle e-readers—and more money (and more professional freedom) rolled in. I’ve watched in delight as over a million dollars dribbled from my salt-stained pen. The only marital problem my wife and I now experience is her jumping up and down while shouting, “Sugar daddy! Sugar daddy!” (Kindles were the major digital techno-advance for us writer’s—now it’s Patreon, for the YouTubers such as S/V Devos.)

And each day at 70 years of age I have the honor of attempting to write something that will live forever. That’s right; I and my salt-stained pen presumptuously and continuously reach for immortality. And each evening, as I re-read what I wrote that day, I realize I’ve actually achieved immorality. Damn, so freak’n close!

(Editor’s note: Fatty and Carolyn are currently in Southeast Asia, on their fourth circ. Fatty is on his 61st year of living aboard, 51 of them with his wife. He continues, after forty plus years, to trade words for money.)

Thanks Captain Fatty for entertaining me for years. I think the one reason I remain a steadfast Cruising World subscriber is that I don’t want to miss one of your columns. Not sure if you remember my inquiry about Scooter Mejia years ago, but you shared some of your Scooter stories with me, all totally believable having spent a few years of my misspent youth in Aspen with Scooter as a housemate. Life is grand.

I love your story! I am reading this because I was researching the Mary Harrigan. She is owned by my estranged cousin Len. The schooner is named after my grandmother and have been curious about her whereabouts. Are you still in contact with him? Susan