When I first sailed into the Lesser Antilles in the late 1970s, Peter Muilenburg was already a legend. The moment I ‘reached’ St. John, United States Virgin Islands, I started scheming on how to get out to the East End to meet him.

My first impression was a shock: he was nothing like I expected. Where was the radical anti-war protester? The Calypso-kissed Merry Prankster? The courageous freedom rider who risked his very life so that others could walk free? The shady South American adventurer with balls of stainless steel? The Old African explorer? The shrewd Yankee Trader with a bilge full of love? The distinguished Dartmouth grad?

I found none of this. What I found was a friend, a truly nice guy, and someone to genuinely look up to.

Human beings are complex. Peter Muilenburg is an especially complex sailor. I could easily paint him as a saint, and just as easily paint him as the devil incarnate—a man who should be locked up and have the key thrown away. But both perspectives would lack perception—and it is my job as a writer to bring clarity and insight, not confusion. So I will start again, on a slightly different tack. Peter Muilenburg became a legend through force of moral will.

Moral will?

Yeah.

I know that sounds kinda strange. What do morals have to do with sailing and cruising and eternally ‘messing around with boats’?

Well, in Peter’s case, everything.

Peter Muilenburg was, and is, a preacher’s son. His whole life is based upon Right and Wrong. In Peter’s world view, there are choices. There is good and evil. You can do the right thing or the wrong thing.

Such a world view could easily translate into a ‘holier than thou’ attitude. Not so, in Muilenburg’s case. In fact, the opposite took place. Peter often falls short of his own mark. Thus, he’s compassionate and sympathetic to sinners—as he knows he is one.

Yes, Peter is a complex beast. He marches to his own drummer. He cares not a wit what polite society thinks—especially a capitalistic culture that values war and violence over peace and love.

In a sense, Peter is an unrepentant hippy who didn’t get the memo that brotherhood went out of style with love beads. He still believes ‘the love you get is equal to the love you give’ as the Beatles sang back in the day. He is a 1960s radical in the sweetest, purest sense of the word—he named one of his sons after Castro, for gosh sakes.

When he hears the term ‘weatherman’, he still thinks ‘Underground’.

To say that Peter and I hit it off would be an understatement. We immediately sensed our common ground. He was … well, a bit of a big brother to me—someone I could go to when I was wrestling with a Big Issue. I just knew he’d never betray a confidence. His personal integrity shone through everything he did.

He served this role of ‘moral counselor’ to many a wayward sailor on St. John. In a sense, he tended to his flock just as his missionary father had in the Philippines. It didn’t matter if you were rich or poor, or black and blue, or white and sad, or liberal or conservative—Peter would be there for you.

… mostly saying nothing, of course, but that’s what a true friend does: listen patiently and compassionately as you work though your own answers.

Peter and I had much in common. We both loved our wives unabashedly. We were family men, first and foremost. We loved sailing and the sea so much we built our own vessels from scratch. And we believed in acting on our beliefs, not just holding them like crystal tea cups.

In Peter’s case, this meant being a Freedom Rider in the Deep South in the early ‘60s—when such activity often resulted in death (if you were lucky) and worse, if you weren’t. (The sadists of the KKK were equal-opportunity torturers.)

This is where Peter developed his taste for hot sauce. Everyone in The Movement back then was poor. There wasn’t much to eat. And sharing was, of course, at the very core of 1960s radicalism.

So Peter always shared his rice and beans with any and all of his fellow travelers—what a shame so many of them didn’t like it so hot-hot-hot!

Of course, at some point the ‘60s died. For me, it was when Nixon was re-elected by a landslide. I, and much of my generation, became disillusioned. We fled ‘back to the farm’.

Peter choose a more watery path—cruising to the Virgins aboard his very basic wooden sailboat in desperate search of Nirvana. Amazingly, he found it in a sleepy place called Coral Bay. He and his wife Dorothy became local school teachers. (Dorothy founded Pine Peace School on St. John, which morphed into Gift Hill and thrives to this day.)

But the past was never far behind Peter. Just when he thought his radical days of protest were over—Richard M. Nixon came to his very doorstep. Suddenly Peter was all over the international news, tacking back and forth in front of the exclusive Caneel Bay resort with a mainsail that read, ‘While Nixon Lazes, Indochina Blazes’!

Peter always put his body (and heart and soul) where his mouth was.

True, protesting with a tiller in one hand and a Pina Colada in the other was a lot better than being locked up in jail and waiting to be lynched by the local racists—but the Lord Works in Mysterious Ways, right?

Sure, Peter was famous for building a boat and sailing it hither and yon—as well as river-traveling in the more remote estuaries of inland Africa. Yes, it was scary when that white-robed witch doctor came aboard (with his many followers) in Gambia—and nearly bled to death on deck demonstrating the infallibility (well, NOT!) of his local amulets.

But mostly what Peter was famous for was being a friend. This is seldom the case. But the more I consider it, the loftier the position of ‘friend’ becomes. Peter wasn’t any kind of a razzle-dazzle leader—yet, on important local issues, his opinion was sought by both continentals and locals alike.

He didn’t say much—and never injected himself into an issue—which made his words carry weight.

One seldom known fact about Peter was that he was such an avid historian. While cruising Spain, he spent much of his time in their national archives, reading firsthand about the Pirate El Draco (Sir Francis Drake) and his ruthless rampage in the Caribbean.

Another aspect of Peter’s multi-faceted character is that, as the years progressed, he became increasingly focused on his writing.

He wrote primarily for SAIL magazine, but his prose also appeared in Reader’s Digest, Caribbean Travel and Life, and, yes, All At Sea.

As a man, Peter was modest. As a writer, however, he dreamed big. And so it is only natural that a man known for his friends would cap off his writing career with an in-depth biography of his best friend … who also just happened to be Man’s Best Friend.

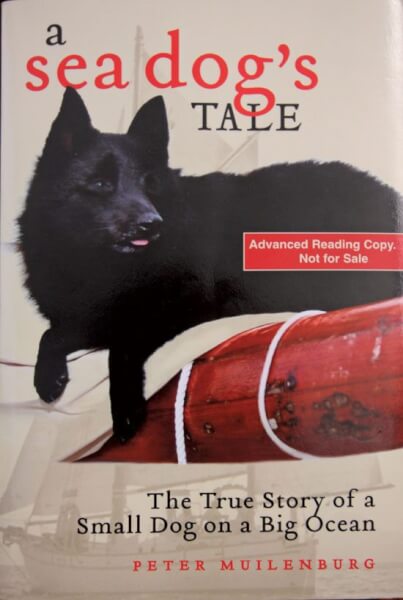

That’s right; Peter Muilenburg’s latest book is a biography of a remarkable dog named Santos. It is entitled A Seadog’s Tale, and subtitled, The True Story of a Small Dog on a Big Ocean.

… well, it is actually about a lot more than just Santos—but the charming, dapper little pure-breed Schipperke is the wonderful, alert, sensitive warm-blooded device Peter uses to tell his sea story … which is infused with love on every page.

I guess every good writer can be summed up in a word—and Muilenburg’s word is LOVE.

I know, I know, we writers are supposed to be notoriously jealous of, and competitive with, each other.

But Peter Muilenburg’s prose hooked me from the moment I read the first sentence—and has never let me down since.

Peter’s writing is like the man himself—lean, sincerely, brave, muscular, and spot-on. He’s a keen observer of life—even through the eyes of a tiny, brave dog.

Me, I’m a cat person. I’d often joke with Peter that I was going to give him a gift certificate from a taxidermist for Christmas—so he could have Santos as a permanent figurehead aboard his beloved Breath.

Peter never took offense—and the mere mention of Santo’s name (regardless of context) would plant a smile on his face.

And, I must admit, Santos was an extraordinary seadog. We sailed many ocean miles together over the years. And I wasn’t the only one who thought he was the smartest member of the crew.

The thing that amazed me most about Santos was, when he was around us humans, he blended right in. He was … well, for all intents and purposes, human. But if another dog showed up, Santos would somehow subtly and effortless shape-shift into, well, an ordinary canine.

… and he was a rascal! Trouble? Oh, Lordy, that dog could get in it, and all the while charming his way through prince and pauper alike.

Most of the stories in this book I originally heard as oral sea yarns in the cockpit of Breath, Peter’s gaff-rigged Paul Johnson-designed double-ended ketch. Dorothy would be passing up conch fritters, and his sons Raff and Diego would be equally aglow at singing the little mutt’s praise.

Santos would listen intently—as if making sure of their veracity.

Mutual friends of ours keep asking me if this (new) book is as good as his previous: Adrift on a Sea of Blue Light. I immediately reread that one (it is right next to my own books on Ganesh’s bookshelf) to make a fresh, comprehensive comparison. Gee, I’m not sure. I guess I will have to re-read both yet again—before jumping to any conclusions.

Editor’s note: Fatty and Carolyn are currently in Trinidad, fixing up their new Wauguiez 43 ketch for circle #3.

Cap’n Fatty Goodlander has lived aboard for 52 of his 60 years, and has circumnavigated twice. He is the author of Chasing the Horizon and numerous other marine books. His latest, Buy, Outfit, and Sail is out now. Visit: fattygoodlander.com