I recently was honored to write the preface to the book Voyaging with Kids. This forced me to sail down memory lane of raising kids aboard a boat. To take an in-depth look at my growing up aboard, and also of raising our daughter Roma Orion aboard.

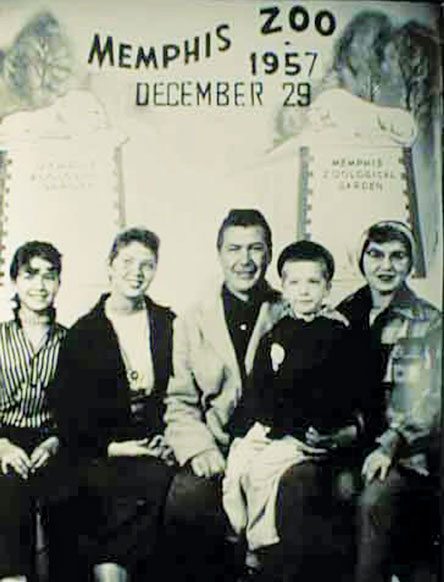

I can’t imagine a more perfect, more idyllic childhood. I grew up aboard the 52ft John G. Alden schooner Elizabeth in the 1950s. It was utter magic. My loving parents were around me 24/7—showing me how to live, not telling me. Morals weren’t something you were taught, they were something you saw in action every day—with our fishermen friends, the shipyard caulkers who metronomed the harbor, our diesel mechanic friends. I wasn’t merely close to my two sisters, I was literally sandwiched between them nightly in the forepeak. Learning was a family affair. My father (a sign painter and commercial artist) taught my sisters to paint, my sisters taught me to read, and my father and mother both (he occasionally wrote for Yachting) encouraged me to write. And they both encouraged all of us siblings to row, sail, and fish.

Fishing was a necessity to put food on our galley table, but it was also fun. Later in life, in a monastery in Thailand, I learned the concept of ‘sanuk’. Sanuk can be explained to Westerners as fun or joy—but it is more than that: it is the ability to find that joy in whatever you do, no matter how ordinary.

The crew of the Elizabeth were masters of sanuk and our family fishing was a perfect example. In the Gulf of Mexico, we’d often gig for flounder at night off the beach. This required dinghies, kerosene lights, sharp gigs, many sloshing buckets—and a ton of laughter. “Stop laughing!” my father would often giggle as he raised his mighty barbed spear in the moonlight. “How can I aim when everyone is making jokes?”

We were a small watery tribe of hunter/gatherers—who hunted fish and gathered smiles and laughter and hugs. Regardless of the scenario, we were always there for each other, and we were often there for others. We were also poor and, thus, shared our love without fear. Penniless, there was no profit in attempting exploitation. Our friends were our friends. We were no one’s profit center. I grew up with a feeling of uniqueness. We were reaching toward freedom, sailing into passion, always fearlessly kissing life full on the lips.

“Who is in charge of our smiles?” my father would ask.

“We are!” we’d sing back.

I must have been nine or ten the first time my father, step-by-step, walked me through taking my first sun sight. “Do it the same way every time, son,” he told me. “Just bring the lower limb of the sun down until it kisses the horizon and then rock the sextant to confirm that it is vertical.”

Nothing stopped us—certainly not lack of money. When we needed a mast, we carved up a lonely telephone pole. Galvanized wire held it up. Our hands were gnarled and bloody from splicing the wire. Sure, we tarred our Manila anchor rode to preserve it. (Using that tarred rode was like grabbing a string of razor blades.) And when we needed new sails, we bought canvas—whole bolts of it—Egyptian cotton, actually, which we cut and sewed ashore on the riverbank. If a windstorm blew down a large highway sign, we knew that plywood was exterior grade and smooth on one side. Who cared if the Marlboro man kept coming back through the paint inside the Elizabeth’s cabinets? Who needed mast track when we could make pearls out of hardwood—and have the fastest dropping sail in the world.

Each of us did their part. I was soon in charge of trimming the wicks and refilling the lamps aboard the Elizabeth. Our running lights and cabin lights were all kerosene that I filled from the spigot of our ten-gallon tank that hung under the cockpit deck beams.

The Elizabeth, built in 1924 at Morse Brothers, had seen better days. We didn’t complain. Hell, we’d only paid $100 for her—as boats tend to be cheap on the bottom. She leaked, of course. That was a given in those days. She had “… more leaks than Eisenhower’s White House,” my father used to joke. We trained ourselves to sleep with one arm hanging downward out of the bunk—a much more dependable method than modern electric bilge sirens. The heavier the sea, the more the Elizabeth opened up. This was common.

Yes, life was hard. Yes, fate could be heartless. Sure, the sea was ‘a cruel mistress’ as my father would tell me a thousand times. But a spell of nice weather, or hooking up a mahi-mahi at dusk, or just sitting around the cockpit singing songs as a family were all the sweeter because of the adversity we faced.

There was only one sin—giving up. Tenacity was our god. We were, above all else, stoic. We were like a cult. If you questioned the wisdom or stupidity of the sea, you were cast out, exiled, and dismissed. “He swallowed the hook,” we’d say, and spit over the side in disgust. Or, even worse, “… turned into a farmer!” we announce with both contempt and derision.

The Next Generation

I honestly believed that my childhood was the pinnacle of happiness—until my wife Carolyn and I started raising our daughter Roma Orion aboard. Suddenly, we could see our salt-stained world anew through her wondrous eyes.

I’ll never forget being boarded offshore by the Trinidadian Navy in 1981 and being quizzed by the enforcement officer.

“How come you have three people on your outward clearance crew list, but there’s just you and your wife?” he asked suspiciously.

“Should I wake up Precious Cargo?” I asked him as I lifted the corner of a pink blanket in the swaying hammock over the galley table.

“Damn,” he said, flipping through Roma Orion’s passport, “only four months old and she already has more stamps than I!”

Last weekend, we sailed to Lazarus Island off Singapore with 35-year-old Roma—along with our two grandchildren, five-year-old Sokú Orion and two-year-old Tessa Maria. Once there, Roma started to teach Sokú how to handle our two-piece kayak, while Tessa Maria stayed in the cockpit and yelled, “Boat, Grandpa, boat!” at everything that moved on the water.

We’d come full circle as a family. It was a lazy day. I yawned and asked Roma, “What’s your favorite thing to do while aboard?”

“Nothing,” she said, like any true sailor would. We all laughed. It’s true. And there’s nothing like family, especially afloat.

Editor’s note: Cap’n Fatty and Carolyn are currently in Durban, resting from their recent 6,000 mile Indian Ocean crossing.

Cap’n Fatty Goodlander and his wife Carolyn are currently on their third circumnavigation. Fatty is the author of Chasing the Horizon and numerous other marine books. His latest, Storm Proofing your Boat, Gear, and Crew, is out now. Visit: fatty goodlander.com